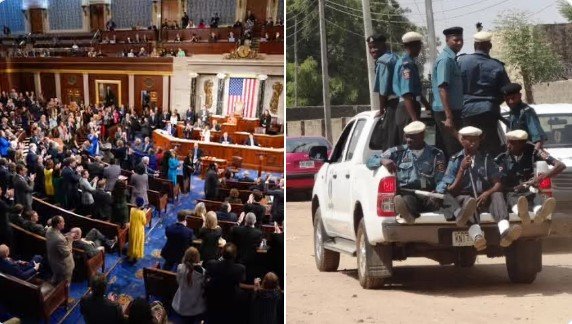

In a heated public rebuttal, the Muslim Rights Concern (MURIC) has strongly rejected claims by Reverend Ezekiel Dachomo — Regional Leader of the Church of Christ in Nations — alleging that the Muslim–Muslim presidency of President Tinubu and Vice-President Kashim Shettima amounts to “Christian genocide.” MURIC accused the cleric of sensationalism, inflammatory rhetoric and disrespect for democratic process, warning that calls for the removal of Shettima amount to undemocratic interference and that any ambition for the seat would have to be pursued through lawful political means in 2027.

The reaction by MURIC comes just days after Dachomo appeared on national television and publicly declared that the presence of both President and Vice-President as Muslims represents “complete genocide to Christians in the political world.” He called for Shettima’s removal and urged Christians to “wake up from their slumber.” MURIC, however, dismissed these claims as baseless, emotive, and politically motivated, describing Dachomo’s statements as “religious hysteria cum religious masturbation” and warning against incitement of sectarian tension.

What Dachomo Claimed — Allegation of “Christian Genocide”

Reverend Dachomo, known for his outspoken criticism of repeated violence allegedly directed at Christian communities, accused the Tinubu-Shettima administration of marginalising Christians. In a televised interview, he alleged that the Muslim–Muslim ticket symbolized a systematic attempt to disenfranchise Christians — framing the leadership arrangement as “complete genocide” against Christians in Nigeria’s political space. He demanded that Shettima be removed from office and claimed that the government was pursuing an “Islamic agenda” with long-term implications for religious freedom and national identity.

Dachomo also pointed to recurring attacks on Christian-dominated communities — particularly in parts of the Middle Belt and the North — as evidence of what he described as a pattern of religious persecution. He has vowed to compile a dossier of such incidents and has threatened legal action, including taking the matter before international bodies, to seek justice for what he alleges is ongoing genocide against Christians.

MURIC’s Response — Rebuffing the Allegations and Warning Against Politicization

In response, MURIC — through its Executive Director — accused Dachomo of overstepping, describing his remarks as inflammatory, unhelpful, and undermining democratic values. MURIC rejected the genocide allegation, arguing that the assertion that the election of a Muslim President and Vice President automatically amounts to genocide is extreme, emotive, and lacks empirical evidence.

MURIC further contended that to suggest the removal of See Vice-President Shettima — who was duly elected via free and credible democratic processes and whose mandate was upheld by appeals and judicial review — is tantamount to rejecting Nigeria’s constitutional democracy. According to MURIC, anyone seeking political office must follow due process; in Dachomo’s case, if he harbors political ambitions, the proper venue would be the 2027 general election, not sensational public outbursts.

The group described the claims as a “denial of the principles of democracy and due process,” and warned that such statements risk exacerbating religious tensions and undermining national cohesion. MURIC urged Nigerians to unite across faith lines against insecurity and criminality rather than stoke religious division.

Why the Debate Matters — Religion, Politics, and National Stability

The exchange touches on a number of sensitive yet critical issues in Nigeria’s political and social landscape:

Religious Representation vs. Allegations of Genocide

Nigeria is characterised by religious diversity, and politics often intersects with religion, ethnicity, and regional identity. While some view the Muslim–Muslim ticket as a routine political outcome following democratic elections, others perceive it as symbolic of marginalisation — particularly in light of recurring communal violence and insecurity. Claims of “genocide” heighten tensions and risk deepening mistrust between religious communities.

Democracy, Electoral Mandates, and Due Process

Elected leaders, including the President and Vice President, derive their mandates from national ballots and, where necessary, judicial validation. Calls to remove them outside constitutional channels challenge democratic norms and could set dangerous precedents. MURIC’s insistence on upholding electoral legitimacy reflects the broader concern about safeguarding democracy and institutional stability.

Security, Violence, and National Healing

Many of the concerns raised by Dachomo stem from real security challenges — attacks on communities, killings, and displacement. However, framing these complex issues solely in religious terms risks oversimplification and misdiagnosis. Experts argue that insecurity in Nigeria involves a mix of factors: criminality, terrorism, resource conflicts, weak governance, and poverty — none of which are exclusively religious. Simplistic or sensational labels could hinder efforts at reconciliation, evidence-based intervention, and justice for all victims.

What’s Next — Potential Fallout and Public Discourse

The controversy is likely to influence public debate in several ways:

- Religious and social discourse — The sharp exchange may deepen religious fault-lines, prompting reactions from Christian groups, Muslim organizations, civil society, and activists.

- Media and public opinion — Social media and mainstream media coverage might intensify, possibly shaping narratives around religious identity, political representation, and national unity.

- Political positioning ahead of 2027 — With MURIC pointing to 2027 for legitimate political contestation, interest in who might run for national office — and on what platform — could rise, especially among religious and regional stakeholders.

- Calls for dialogue and reconciliation — The controversy may encourage leaders across faiths to engage in interreligious dialogue, emphasise inclusive governance, and address underlying grievances over security, development, and representation.

Conclusion: Tension Between Fear, Faith, and Politics

The clash between Reverend Ezekiel Dachomo’s stark allegation of Christian genocide and MURIC’s forceful rejection underscores the fragility of religious-political discourse in Nigeria. On one hand, real feelings of fear, mistrust and marginalisation drive calls for urgent redress — on the other, national institutions and civil-society stakeholders warn against politicising religion and undermining democratic norms.

As the nation wrestles with insecurity, economic hardship, and social division, the leadership of religious bodies, advocacy groups and government alike will have a crucial role to play. Ultimately, how Nigeria responds — whether with reconciliation, inclusive policy-making, transparent justice and respect for diversity — may determine whether the rhetoric of grievance becomes a foundation for healing or a trigger for deeper division.

For now, one thing remains clear: the debate sparked by Dachomo and MURIC has laid bare unresolved questions about faith, governance and belonging in Nigeria.