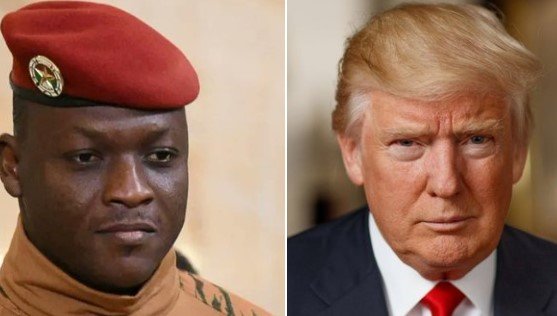

In a firm assertion of national sovereignty, Burkina Faso’s ruling military government has rejected a United States plan to deport migrants to its territory. The announcement, which surfaced amid rising tension over Washington’s controversial “third-country deportation” programme, marks another African nation pushing back against a U.S. policy widely criticised by human rights groups and regional observers.

Burkina Faso’s Position: A Firm “No” to U.S. Deportation Plans

Officials in Ouagadougou confirmed that the government has no intention of becoming a host for migrants deported from the United States. The junta, which seized power in 2022, stated that such a move would violate national interests and burden a country already battling internal security challenges.

According to sources within Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the government was approached by U.S. representatives earlier this year about a possible agreement to accept certain categories of migrants who could not be sent back to their countries of origin. The Burkinabé authorities reportedly declined the offer, citing sovereignty, security risks, and humanitarian concerns.

Understanding the U.S. “Third-Country Deportation” Policy

The U.S. third-country deportation programme allows Washington to send migrants to nations other than their own when legal or diplomatic obstacles prevent deportation to their home countries. In practice, this means that a person detained in the U.S. could be relocated to another nation—often in Africa—under a bilateral agreement.

The policy, initially implemented as part of an effort to reduce backlogs in immigration detention, has been described by critics as “outsourcing” the American immigration problem. Some African nations, such as Rwanda and Eswatini, have reportedly agreed to host small numbers of deportees under confidential arrangements that include financial compensation or development aid.

However, the programme has been met with fierce criticism from international human rights organisations. They argue that transferring migrants to third countries where they have no legal ties, family, or community support violates international norms and exposes them to potential abuse and indefinite detention.

Burkina Faso’s Security and Humanitarian Context

Burkina Faso’s refusal is also rooted in its current domestic situation. The country has been engulfed in a prolonged conflict with jihadist groups linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State since 2015. The violence has displaced more than two million people internally and placed enormous strain on the government’s ability to provide security and social services.

Analysts note that accepting foreign deportees at this time would exacerbate existing pressures on the state. “Burkina Faso is struggling to resettle its own displaced citizens. Hosting migrants from other parts of the world would be logistically and politically unmanageable,” said a regional security expert in Ouagadougou.

The junta has also been pursuing an assertive foreign policy aimed at reducing Western influence while strengthening ties with Russia and neighbouring Sahel states under similar military-led governments. Rejecting U.S. deportees fits this pattern of defiance and reinforces the junta’s image as a government unwilling to bow to foreign demands.

African Resistance to U.S. Deportation Agreements

Burkina Faso is not alone in its opposition. Several African countries have recently resisted similar U.S. overtures. Nigeria, for instance, publicly rejected pressure to accept deportees of non-Nigerian origin, arguing that the proposal was “unacceptable and inconsistent with international law.”

Other African governments have expressed concerns more discreetly, wary of losing U.S. aid or trade privileges. Yet, across the continent, there is a growing sentiment that Africa should not serve as a dumping ground for migrants and detainees from Western nations.

In East Africa, Rwanda and Uganda have faced sharp criticism over their involvement in related deportation or resettlement schemes—both with the U.S. and the United Kingdom. Human rights advocates argue these deals often lack transparency and fail to guarantee basic protections for those relocated.

Human Rights and Legal Concerns

Legal experts contend that the U.S. third-country policy raises serious questions under international law. The principle of non-refoulement, enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention, prohibits sending individuals to countries where they may face persecution or where their safety cannot be guaranteed.

Furthermore, deportees sent to third countries often have no legal status or rights in their new host nation. Without clear agreements guaranteeing their welfare, they risk being detained indefinitely, denied access to lawyers, or even expelled again to another country.

Human rights organisations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have called on the U.S. to abandon the policy, arguing that it undermines America’s global reputation as a defender of human rights. They insist that migrants should be processed in accordance with due process and have access to asylum where applicable.

Diplomatic Implications

Burkina Faso’s decision could further strain its already delicate relations with Washington. Since the 2022 coup, the U.S. has imposed limited sanctions on the country’s military leaders and suspended some non-humanitarian aid. The junta’s growing closeness with Moscow, coupled with its expulsion of French troops and withdrawal from the G5 Sahel alliance, has deepened its isolation from traditional Western allies.

However, analysts suggest the junta sees political benefit in rejecting Western overtures that could be perceived as neo-colonial. “Saying no to the United States plays well domestically,” said an African political observer. “It allows the leadership to present itself as defending national dignity against foreign interference.”

The Broader Picture: Migration Politics and African Sovereignty

The controversy over third-country deportations taps into a broader debate about African sovereignty and the continent’s role in global migration management. Many African nations argue that they are being unfairly pressured into accepting migrants from other regions in exchange for economic aid or diplomatic favours.

This dynamic reflects deeper structural inequalities in the international migration system. Wealthy nations, particularly in Europe and North America, often design policies to externalise their border controls, transferring responsibility to poorer countries that lack the capacity to protect migrants effectively.

Burkina Faso’s defiance is therefore seen not merely as a rejection of a single deportation plan, but as part of a wider assertion of Africa’s right to set its own migration and security policies.

Conclusion: A Defining Moment in Africa–U.S. Migration Relations

Burkina Faso’s refusal to participate in the U.S. third-country deportation programme highlights the growing backlash across Africa against policies perceived as exploitative and unjust. With several other nations reconsidering their positions, Washington faces mounting diplomatic challenges in maintaining this controversial strategy.

As the debate continues, Burkina Faso’s stance sends a clear message: African countries will not be passive participants in international migration politics. For the junta in Ouagadougou, rejecting the U.S. plan is both a statement of independence and a reflection of domestic realities — a nation still fighting to secure its borders, rebuild its economy, and assert control over its future.